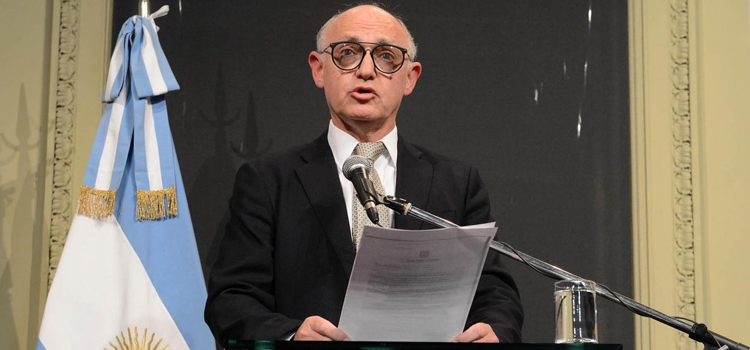

“Soy un prisionero político”, la denuncia del excanciller argentino Héctor Timerman por el caso AMIA

«Soy un prisionero político»: la columna de Héctor Timerman en The New York Times

Escribo estas líneas desde mi casa, a donde me ha confinado el tribunal durante más de una semana. Soy un preso político. Un juez argentino me acusó de traición y del encubrimiento de funcionarios iraníes acusados de ser los autores intelectuales del ataque terrorista de 1994 en contra de la Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina (AMIA), el principal centro judío de Buenos Aires, en el que fallecieron 85 personas y 300 resultaron heridas. A veintitrés años del ataque, no hay detenidos y se sabe muy poco de los hechos, excepto que sucedieron.

La investigación sobre el ataque fue tan defectuosa y corrupta que en 2004 se anuló el juicio y se comenzó a investigar al juez que lo presidía. El juez Claudio Bonadio —quien ahora me acusa de traición— dirigió la investigación de aquel encubrimiento, pero lo retiraron del caso en 2005, acusado de ser tendencioso y de haberse coludido para proteger a quienes frustraron la investigación inicial.

El fiscal Alberto Nisman tomó el mando de la investigación de la AMIA y señaló a un grupo de funcionarios iraníes como autores intelectuales del ataque. Los tribunales ordenaron la aprehensión de los sospechosos y exigieron su presencia ante un juez, puesto que la ley argentina no permite los juicios en ausencia. Irán argumentó que sus leyes prohíben la extradición de sus ciudadanos. Por lo tanto, el caso siguió paralizado durante una década más.

Tener avances en el caso era una meta clave para el gobierno de la expresidenta Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, en el que trabajé como canciller de 2010 a 2015. La solución consistió en un acuerdo entre ambos países: un juez argentino interrogaría a los sospechosos en Irán e iniciaría los procedimientos judiciales para llegar a la verdad y darle justicia a las víctimas. Además se establecía la creación de una comisión de la verdad no vinculante compuesta por juristas internacionales que atendieran el caso. Para Bonadio, el acuerdo debilita la investigación criminal del caso de la AMIA y es el pretexto para mi acusación.

La traición es una acusación sin precedentes relevantes en la historia moderna de nuestro país. Para que un ciudadano argentino pudiera cometer traición, el país tendría que estar en guerra. Argentina e Irán no están en guerra y nunca lo han estado. Al día de hoy, conservan sus relaciones diplomáticas. No obstante, Bonadio justificó su acusación al decir que el ataque terrorista representa un acto de guerra. Arguye que el país ha estado en guerra durante veintitrés años, sin que se haya reconocido oficialmente, y contradiciendo toda jurisprudencia.

Irán niega las acusaciones en contra de sus ciudadanos, pero accedió a cooperar en el caso luego de una campaña diplomática que duró años dirigida por los gobiernos sucesivos de Kirchner. Así comenzaron las negociaciones oficiales (anunciadas por Fernández de Kirchner en las Naciones Unidas) y los ataques políticos perpetrados por quienes afirmaron que Irán era una contraparte inaceptable para la negociación. Ciertos grupos en Argentina parecen preferir la parálisis, quizá por el temor a que no haya suficiente evidencia para condenar a los sospechosos iraníes.

El caso en contra del gobierno de Fernández de Kirchner reitera las acusaciones, rechazadas por las cortes argentinas ese mismo año, que había hecho Nisman unos días antes de su muerte: que el acuerdo, ratificado por el congreso argentino, tenía el propósito secreto de encubrir la supuesta participación de los iraníes. Las acusaciones estaban forzadas, en parte porque aparecieron reportes falsos en los medios de comunicación que hablaban de que me había reunido en secreto en Alepo, Siria, con Ali Akbar Salehi, quien en ese momento era ministro de Relaciones Exteriores de Irán. En efecto, viajé a Alepo, donde me reuní con el presidente de Siria, Bashar al Asad —una reunión que, lejos de ser secreta, se documentó en comunicados diplomáticos y reportes en la prensa argentina—, pero no me reuní con Salehi durante mi estancia ni se presentaron pruebas fehacientes que sustentaran dicha acusación. El resto de las acusaciones en el caso se construyeron a partir de esta mentira, que niego categóricamente.

Una parte vital de las acusaciones de Nisman está relacionada con las alertas rojas de la Interpol, una especie de orden de aprehensión cuyo objetivo es ayudar a las fuerzas policiales nacionales a localizar a los involucrados en casos criminales de interés internacional. Nisman, y ahora Bonadio, me acusan de eliminar estas alertas rojas pero, hasta hoy, no han sido modificadas. Me preocupó que esto hubiera podido suceder, ya que las alertas contribuyen a garantizar el cumplimiento por parte de Irán. El que entonces era el secretario general de la Interpol, Ronald Noble, negó que Argentina hubiera solicitado algún cambio en las alertas rojas inmediatamente después de que Nisman diera a conocer su fallo y Noble ha mantenido su postura de manera enfática. En lugar de aceptar sus declaraciones, Bonadio acusa a Noble de estar coludido en este supuesto encubrimiento.

No sé por qué el acuerdo se ha convertido en el centro de tal ira vengativa. No puedo entender por qué Bonadio parece determinado a perseguir el caso con evidencias tan endebles, ni por qué ha anunciado decisiones con una sincronía política tan sospechosa. Pero lo que sí sé es que se le acusa de intentar proteger a sus exaliados políticos, quienes estaban en la mira de las indagaciones relacionadas con la primera investigación de la AMIA.

Durante mucho tiempo Bonadio fue activista del Partido Justicialista. Cuando el presidente Carlos Menem nombró a Carlos Corach ministro del Interior —el puesto requiere que gestione la relación con todos los gobernadores, los miembros del parlamento, las fuerzas de seguridad y la rama judicial—, colocó a Bonadio en el secretariado de asuntos jurídicos.

En 1994, poco antes del ataque a la AMIA, Corach lo ascendió a una magistratura federal. Subió al puesto sin presentarse a las oposiciones contra otros candidatos, como lo exigen los procedimientos en Argentina. En 2005, los funcionarios judiciales lo separaron del primer juicio que investigaba el encubrimiento del caso de la AMIA por haber mantenido el caso paralizado durante cinco años. Uno de los acusados era Corach.

El gobierno del presidente Néstor Kirchner acusó a Bonadio de un desempeño mediocre y buscó la manera de eliminarlo de la magistratura. En 2010, Nisman acusó a Bonadio de amenazarlo para que afirmara que la investigación de la AMIA no involucraba a sus aliados. En un sentido más amplio, es el juez en funciones con más quejas en el país: ha acumulado al menos cincuenta reportes de mala praxis a lo largo de los años.

Desde que Mauricio Macri asumió la presidencia a finales de 2015, Bonadio ha logrado encabezar la mayoría de los casos en contra de Fernández de Kirchner y ha declarado prisión preventiva para muchos de sus exfuncionarios.

El Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales, una famosa organización que defiende los derechos de los argentinos, ha criticado esta medida y afirma que se trata de una “instrumentalización del sistema penal para perseguir a opositores políticos”.

Bonadio ha rechazado la solicitud de liberarme del arresto, que al parecer podría durar mucho tiempo. Hace unos días, decidió que debo solicitar permiso para ser atendido por los médicos, una decisión que criticó Human Rights Watch.

Tristemente, no es la primera vez que mi familia es víctima de una persecución política. Hace cuarenta años, mi padre, el periodista Jacobo Timerman, también fue prisionero político. Pasó casi un año en arresto domiciliario, luego de ser secuestrado y torturado en centros clandestinos dirigidos por la milicia durante la última dictadura de mi país, de 1976 a 1983.

La defensa de los derechos humanos ha tenido una importancia crucial en mi vida personal y profesional. Considero que mi cargo diplomático en este caso era parte de ese ideal. En cambio, me encuentro inmerso en un proceso kafkiano que agrava el cáncer que padezco y me roba el tiempo que me queda de vida.

Por ahora, el caso de la AMIA se diluye, tal como ha sucedido durante décadas, y quienes buscamos, de buena fe, justicia somos el blanco de la furia de la comunidad judía y de las numerosas familias de las víctimas.

He solicitado que se me juzgue lo más rápido posible. Evitar que reciba atención médica a tiempo es casi como condenarme a la muerte. La Constitución argentina no contempla la pena de muerte pero, con un juez como este, no tengo garantía de ello.

I Am a Political Prisoner in Argentina

I write these lines from my home, where I have been confined by the courts for more than a week. I’m a political prisoner. An Argentine judge accused me of treason, and covering up for Iranian officials accused of masterminding the 1994 terrorist attack against the ArgentineIsraeli Mutual Association, or AMIA, Buenos Aires’ principal Jewish center, in which 85 people died and 300 were wounded. Twenty-three years after the attack, nobody has been convicted and few facts have been established other than that it occurred.

The investigation into the attack was so flawed and corrupt that in 2004 the entire trial was annulled and the judge who led it was put under investigation. Judge Claudio Bonadio — who now accuses me of treason — led the investigation into that cover-up, but was removed from it in 2005, charged with partiality and colluding to protect those who thwarted the initial investigation.

The prosecutor Alberto Nisman took charge of the AMIA investigation and pointed to a group of Iranian officials as the masterminds of the attack. The courts ordered that the suspects be apprehended and brought before a judge, as Argentinian law does not permit trials in absentia. Iran countered that its own laws forbid the extradition of its citizens. Thus, the case remained paralyzed for another decade.

Advancing the case was a key goal of the former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s administration, in which I served as foreign minister from 2010 to 2015. The solution was an agreement between both countries: an Argentine judge would question the suspects in Iran and begin judicial proceedings to bring truth and justice to the victims. It also established a nonbinding truth commission composed of international jurists to observe the case. For Mr. Bonadio, the agreement undermines the criminal investigation in the AMIA case and is the pretext for my indictment.

Treason is an accusation without relevant modern precedent in our country. For an Argentine citizen to commit treason, the country must be in a state of war. Argentina and Iran are not, and never have been, at war. To this day, they maintain diplomatic relations. Nonetheless, Mr. Bonadio justifies this accusation by contending that the terrorist attack represents an act of war. He argues that the country has been at war for 23 years, without any formal acknowledgment, and in contradiction of all jurisprudence.

Iran rejects the accusations against its citizens. Nonetheless, it agreed to cooperate in the case after a multiyear diplomatic campaign led by the successive Kirchner governments. Thus began the official negotiations — announced by Ms. Fernández de Kirchner in the United Nations — and the political attacks by those who said Iran was an unacceptable negotiating partner. Certain groups in Argentina seemed to prefer paralysis, perhaps out of fear that there is insufficient evidence to condemn the Iranian suspects.

The case against the Kirchner administration reiterates the accusations made by Mr. Nisman a few days before his death that were dismissed by Argentinian courts that same year: that the agreement, ratified by Argentina’s congress, secretly aimed to cover up the alleged role of the Iranians. The accusations are cobbled together, in part, from false media reports alleging a secret meeting in Aleppo, Syria, between me and Ali Akbar Salehi, who at that time was Iran’s foreign minister. I did indeed travel to Aleppo, where I met with President Bashar al-Assad of Syria — a meeting that, far from secret, was documented in diplomatic cables and reported in the Argentinian press — but I did not meet with Mr. Salehi while I was there, and no credible evidence has been presented to support this falsehood. The rest of the allegations in the case were built on this lie, which I categorically deny.

A central part of Mr. Nisman’s accusations involve the Interpol red notices, a form of arrest warrant that aims to assist national police forces to locate those wanted internationally in criminal cases. Mr. Nisman, and now Mr. Bonadio, accused me of aiming to remove these red notices. Yet, to this day, they remain unchanged. I was anxious that this be the case, as they served to ensure Iranian compliance. The then-secretary general of Interpol, Ronald Noble, denied that Argentina requested any change in the red notices immediately after Mr. Nisman made his accusation, and Mr. Noble has maintained that position emphatically. Instead of accepting his statements, Mr. Bonadio now accuses Mr. Noble of colluding over the claimed cover-up.

I do not know why the agreement has become the focus of such vindictive anger. I cannot say why Mr. Bonadio seems determined to pursue a case with such flimsy evidence, and why he has announced decisions with suspiciously political timing. But I do know that he is accused of attempting to shield former political allies investigated in the original AMIA investigation.

Mr. Bonadio was a longtime Partido Justicialista (Peronist) activist. When Carlos Corach was appointed minister of the interior by President Carlos Menem — the position included managing relations with all the governors, Parliament, security forces and the judicial branch — he placed Mr. Bonadio in the secretariat of legal affairs.

In 1994 (shortly before the AMIA attack), Mr. Corach promoted him to federal judgeship. He got the position without passing through a competition with other candidates, as is the procedure in Argentina. In 2005, the judicial authorities separated him from the first trial investigating the cover-up the AMIA case, for having kept the case paralyzed for five years. One of the accused was Mr. Corach.

President Néstor Kirchner’s government accused Mr. Bonadio of poor performance and sought to have him removed from the bench. In 2010, Mr. Nisman accused Mr. Bonadio of threatening him to ensure AMIA investigation did not involve the judge’s allies. More broadly, he is the sitting judge with the most complaints in the country — he has collected at least 50 reports of misconduct over the years.

Since Mauricio Macri assumed the presidency at the end of 2015, Mr. Bonadio has managed to head most of the cases against Ms. Fernández de Kirchner and has imprisoned several of her former officials in pretrial detention.

The Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales, a well-known Argentinian rights organization, has criticized the use of this measure, saying it represents the “use of the penal system to persecute political opponents.”

Mr. Bonadio has rejected a request to release me from detention, which apparently could continue for a long time. And a few days ago, he determined that I must ask for permission to see doctors, a decision criticized by Human Rights Watch.

Sadly, it is not the first time my family ihas been a victim of political persecution. Forty years ago, my father, the journalist Jacobo Timerman, was also a political prisoner. He spent over a year under house arrest, after being kidnapped and tortured in clandestine centers run by the military during my country’s last dictatorship from 1976 to 1983.

Defense of human rights has been vitally important in my personal and professional life. I considered my diplomacy in this case to be part of that ideal. Instead, I find myself enmeshed in a Kafkaesque process that aggravates my cancer and robs me of the time I have left.

For now, the AMIA case languishes, as it has for decades. And we who in good faith sought justice are the targets of the anger of the Jewish community and many families of the victims.

I have asked to be judged as quickly as possible. Preventing me from getting timely medical attention is like condemning me to death. Argentina’s Constitution does not permit the death penalty. But with a judge like this, that is little guarantee.